The Storm that changed Australia

Cyclone Tracy's impact on Darwin

The chapter begins with a broad overview of this extraordinary disaster and its immediate aftermath in Darwin. It then proceeds to a series of small illustrated examination of some of the details such as the track of the cyclone, the evacuation of Darwin etc. It finished with a short introduction to two books published by the Society of cyclone stories.

On Christmas Eve 1974, one of the most devastating natural disasters in Australian history struck the city of Darwin. This event was Cyclone Tracy, a powerful tropical cyclone that left an indelible mark on the city and its people. Cyclone Tracy's fury and the subsequent efforts to rebuild the city are a testament to human resilience in the face of nature's might.

Cyclones are a large-scale air mass that rotates around a strong centre of low atmospheric pressure. In the Southern Hemisphere, cyclones like Tracy rotate clockwise, but on the northern side of the equator, they rotate anti-clockwise. Cyclones are massive storms that can bring heavy rain, strong winds, and storm surges (which means extra-high tides). They can cause massive damage, as the residents of Darwin found out in 1974.

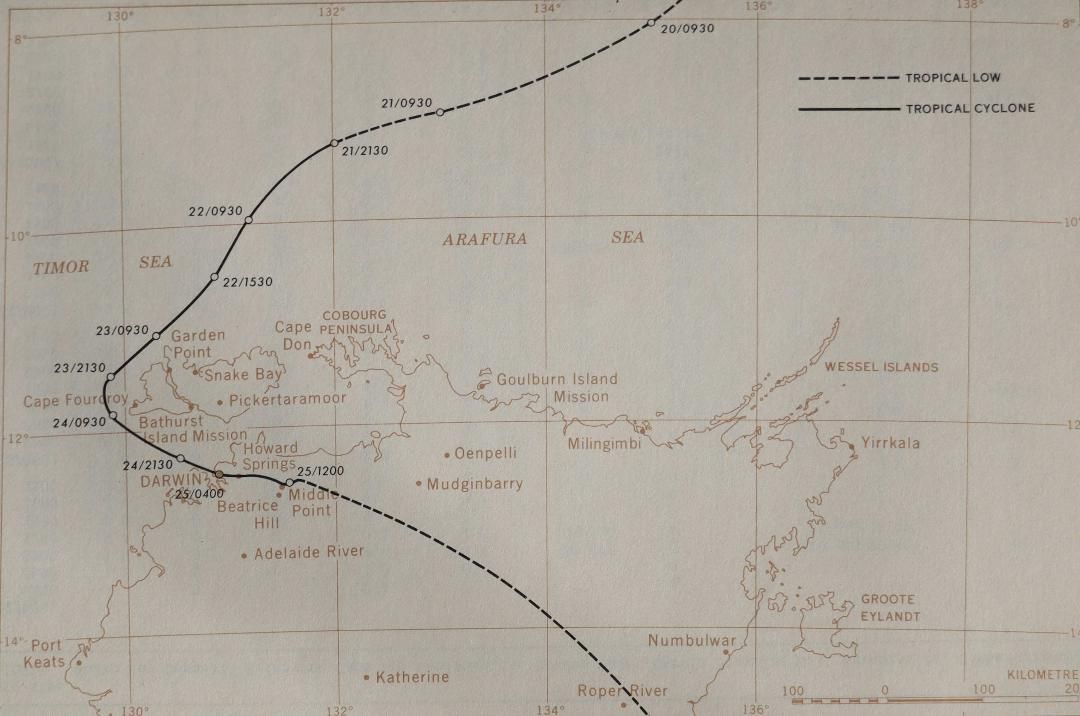

Cyclone Tracy began forming on December 20, 1974, over the Arafura Sea, to the northeast of Darwin. Initially, it was just a tropical low-pressure system, but by December 21, it had intensified into a tropical cyclone. Cyclones are classified into categories from 1 to 5, with Category 5 being the most severe. Tracy was a Category 4 cyclone when it made landfall. Few people were prepared for Tracy. Two weeks earlier a different cyclone, named Selma, had come, and gone without any ill-effects, and people were more interested in celebrating Christmas than battening down their houses. Although there were several warnings, most of the people of Darwin did not evacuate or prepare for the cyclone.

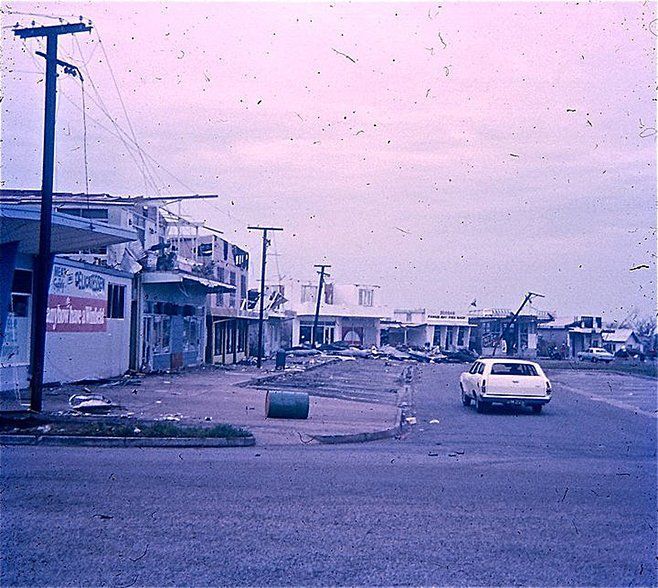

Then, Cyclone Tracy reached Darwin. The city had experienced cyclones before, in fact it was destroyed by them in 1897 and 1937, but nothing could have prepared its residents for what was about to happen. Tracy was a ‘nasty little cyclone’ that was relatively small in size, with a diameter of about 48 kilometres, but it was extremely intense. Wind speeds were recorded at 217 kilometres per hour, but some estimates suggest they could have been as high as 240 kilometres per hour (150 miles per hour). We don’t know exactly because the anemometer at the Bureau of Meteorology broke in the high wind. The cyclone struck in the early hours of Christmas Day, causing catastrophic damage. Buildings were torn apart, power lines were downed, and trees were uprooted. The sound of the wind was described as a roar, like a freight train passing by. People who sought shelter in their homes found themselves exposed as walls and roofs were ripped away.

Many houses had nothing left except the elevated floor – these were soon to be called the ‘Darwin dancefloors.’ Thousands of people were injured – many were cut by flying debris like corrugated iron. Some were sand blasted by the wind. Sixty-six people were killed - 45 died on land and 21 died at sea.

By dawn, much of Darwin was unrecognizable because of the overwhelming destruction. Approximately 70 percent of Darwin’s buildings were destroyed or severely damaged, including most of the homes. The city’s infrastructure was in ruins, with no electricity, water, or communications. In the immediate aftermath, the response was swift. The Australian government, led by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, declared a state of emergency, and initiated a massive relief and evacuation operation. Over 20,000 people, about two-thirds of the city's population, were evacuated to other parts of Australia by plane. This was one of the largest airlifts in Australian history. Another 10,00 people jumped into cars and trucks that were still drivable, and headed south, down the Stuart Highway.

The city then needed to be rebuilt. It was a monumental task that took several years, overseen by the Darwin Reconstruction Commission. Strict building codes were introduced to ensure that future cyclones could not be so destructive. One simple improvement was the introduction of screws to hold down corrugated iron roofing sheets, rather than nails.

Today, Darwin is a modern city with buildings designed to endure the harsh climate of northern Australia. Cyclone Tracy was Australia’s worst natural disaster, and it remains a significant event in Australia's history. People still talk of life ‘before Tracy’ or ‘after Tracy’.

The cyclone taught many valuable lessons about disaster preparedness and response. The importance of early warning systems, robust infrastructure, and effective emergency management became clear. Advances in meteorology and technology have since improved the ability to predict and prepare for cyclones, and this will save lives and reduce damage in future events.

More information and articles about the Cyclone

We were there: Historical Society book publications of Cyclone Tracy Stories.

The Historical Society has had two Cyclone Tracy manuscripts submitted to it which we were very pleased to publish. They are first hand accounts that, for historians, are always important. As Phillip Carson wrote in the forward to ‘The Not So Silent Night’, ‘the compelling rawness of these first hand accounts make gripping reading’.

Cyclone Tracy was a disaster that stunned the nation. Perhaps in retrospect, a prelude to the climate change events that Australia would begin to experience. But it remains an event that some 50 years later still looms large for many Darwin people. As Sue Sayers has written, ‘a night of superlatives, the biggest natural disaster for Australia, the largest peacetime evacuation, the most people packed into a 747 Jumbo aircraft and it was also a time when many unknown people behaved in exceptional ways’.

The following two books bring that night and its aftermath alive again.

Acknowledgement of country

The Historical Society of the Northern Territory acknowledges the Larrakia people, the Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land on which History House stands, and acknowledges their continuing connection to land, sea, and community. We pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging.

Daly Waters, Hayfield Station & Newcastle Waters July 2023

Field Trip 27-30 July 2023 - Daly Waters, Hayfield Station, Newcastle Waters & Elliott Regions by Bev Phelts

VRD Region - July 2022

Field trip to Victoria River Region - Augustus Gregory National Park & beyond by Bev Phelts

Southport to Adelaide River - June 2021

Day trip - the 4WD track from Southport to Adelaide River - 20 June 2021 by Bev Phelts

Channel Island Leprosarium & Middle Arm - July 2020

Day Trip to Channel Island

Leprosarium and Middle Arm

25 July 2020 by Bev Phelts

South Alligator River Region & Goldfields Loop -July 2019

Field Trip 26-28 July 2019

South Alligator River Valley and

Mt Wells Goldfields Loop Road

by Bev Phelts

Darwin to Nhulunbuy- July 2018

Field trip Darwin to Nhulunbuy (Gove) - 26-31 July 2018 by Bev Phelts

The Murranji Track- July 2017

Field trip - the Murranji Track (Ghost Road of the Drovers)

28-30 July 2017 by Bev Phelts

Oenpelli & Maningrida - July 2016

Field Trip to Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) and Maningrida, Arnhem Land - 22-24 July 2016 by Bev Phelts

The Tiwi Remembers- June 2016

Day trip to Bathurst Island (Warrumiyanga). The Tiwi remembers the 75th Anniversary of the bombing of Darwin. Events included the unveiling of statue of the Tiwi man who captured the first Japanese soldier on Australian soil.

Katherine & Beyond - July 2015

Katherine and Beyond – Emungalan, Manbulloo & the graves of William Light & Matt Cahill - 24-26 July 2015 by Bev Phelts

Copper Mine, Daly River area - September 2014

Day trip to the Copper Mine, near Mt Hayward, Daly River area - 14 September 2014 by Bev Phelts

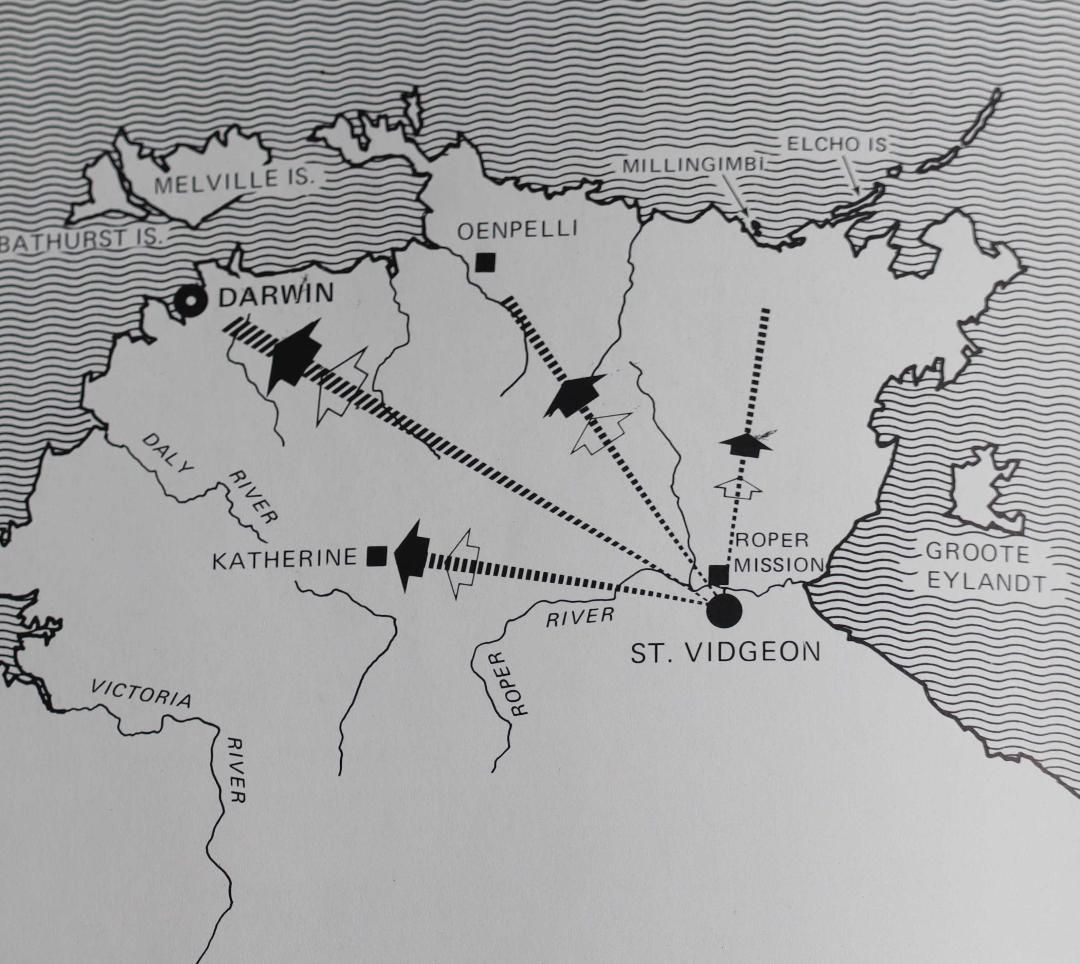

Roper River Valley - July 2014

Field trip to Historic Sites & Landscapes in the Lower Roper River Valley - 24-28 July 2014 by Bev Phelts

Rosewood, Kildurk & Lissadell Stations,- July 2013

Field Trip to Rosewood, Kildurk & Lissadell Stations, 26-29 July 2013 by Bev Phelts

140th Anniversary of the OLT - August 2012

Celebrating the 140th anniversary of the Overland Telegraph Line - August 2012 by Bev Phelts

John McDouall Stuart & party - July 2012

Celebrating the 150th Anniversary of the south to north expedition - John McDouall Stuart & his party - July 2012 by Bev Phelts

Fort Wellington, Cobourg Peninsula - July 2008

Field trip to Fort Wellington, Raffles Bay, Cobourg Peninsula - 24-27 July 2008 by Bev Phelts

Pine Creek Region July 2024

Field Trip 26-28 July 2024 - Burrundie, Mt Wells tin mine, Springhill, WW11 McDonald Airfield, Copperfield Dam & Umbawarra Gorge.

All images on this site courtesy of Library and Archives NT and personal collections of members of the HSNT